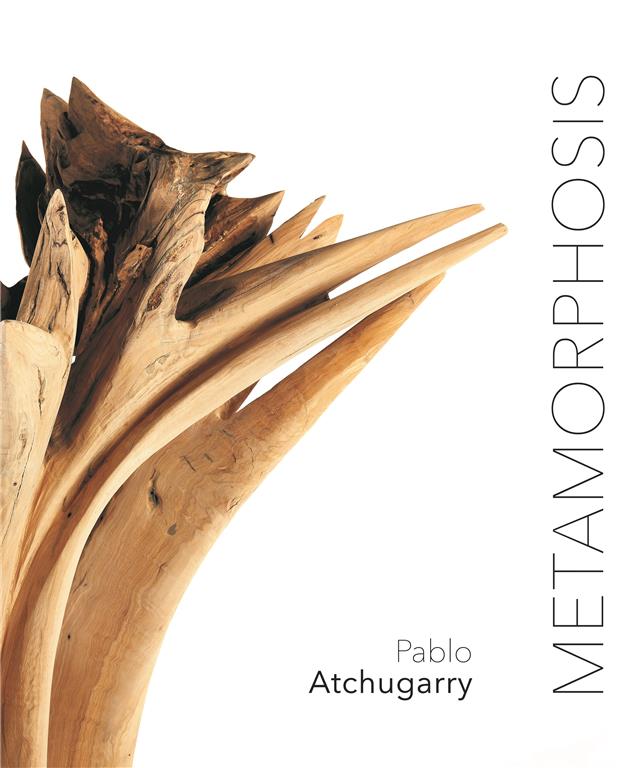

METAMORPHOSIS – Pablo ATCHUGARRY

15/10/2021 – 28/02/2022

Gallerist Adriano Ribolzi asked Pablo Atchugarry to give life to these metamorphoses from olive wood, a sacred tree, important for the nourishment it provides and striking in its structure. The challenge is not to sculpt but to guess, to follow nature in its most spontaneous expressions and, at the same time, to guide it towards a shape, a story, that is that of the magic of Art.

Six wooden sculptures carved from the trunks of century-old olive trees. The forest of Pablo Atchugarry is filled with mytholigies, sylvester motifs and starry constellations.The sculptures tell tales and myths that from Antiquity reach us directly inspired from Book I of Ovid’s Metamorphsis.

You have probably already heard about Ovid’s Metamorphosis, either in school, or because your intellectual curiosity is alert, or because Antiquity raises in you a great interest or simply because it is an unavoidable source of inspiration. All the myths of Antiquity have travelled from the greco-roman era until our days thanks to this Noah’s arch represented by Ovid’s poems, and thanks to which we can say « What a Narcissist! » to our friend who admires his own image on a mobile screen. Power of art is unbelievable ; it can fill seculary distances otherwise insurmountable.

Pablo Atchugarry, the giant of contemporary sculpture, retrieves here primordial materials. For a moment, he sets marble aside in order to consider wood, a simple material that simultaneously conveys strength and weakness, particularly after recent events like the frightful fires that have ravaged the Amazon forest.

Gallerist Adriano Ribolzi asked Pablo Atchugarry to give life to these metamorphoses from olive wood, a sacred tree, important for the nourishment it provides and striking in its structure. The challenge is not to sculpt but to guess, to follow nature in its most spontaneous expressions and, at the same time, to guide it towards a shape, a story, that is that of the magic of Art.

This, then, is more a reflection than an exhibition, more a prayer than an indictment. Pablo Atchugarry has always sculpted shapes inspired by nature, shapes from which they have drawn their sinuousness and importance. But this time, when working on commission from Adriano Ribolzi, Pablo takes the time to observe the material and removes instead of adding. And if he never stops smoothing down the wood, which contrary to the marble keeps its roughness and the shape – rather than getting its inspiration from nature – is reminiscent of the anthropomorphic world. These sculptures can therefore be compared to bodies undergoing metamorphosis becoming the protagonists of the myths that we are about to narrate.

PROMETHEUS

We are dealing with verses 76-88 of Book I of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The titan Prometheus, whose name literally means “he who comes first”, steals fire from Zeus in order to give it to human beings.

Throughout Western art, Prometheus is depicted as the embodiment of rebellion and of release from imposed power. Zeus sentences Prometheus to undergo horrific tortures, but in the end it is the rebel who wins, not the one in power. This trunk, weighing over 300 kg, is in itself a titanic Prometheus. Its large, solid shape captures the viewer’s gaze, conveying a sense of vigour, strength, and power. This contemporary yet at the same time very ancient Prometheus combines different levels and shapes; it regains its natural appearance while at the same time changing, transforming into something which ceases to be a mere tree trunk to become a sculpture and work of art. Atchugarry simply draws this shape out from the wood, just as Michelangelo would see forms emerge from marble. Here, more than in any other sculpture, we can detect the connection between the marble work and the transition to wood, through the shapes and carving, particularly in the lower section of the trunk. We find the sculptor’s reflection on motion, which begins here and marks all six pieces on display.

THE AGES OF MAN

Immediately after recounting the tale of Prometheus, in verses 89-150 of the Book I Ovid describes the myth of the ages of man. Prometheus is also the creator of the human race, which was fashioned from the image of the gods. Unlike other beings, who look down, man was created to look up – to the stars. This marked the spontaneous beginning of the period of time known as the “Golden Age”, an ancient time in which there were no laws because everything was wonderful. However, this age soon degenerated into the subsequent ones, down to the Iron Age, which brought war. However, Pablo stops at the static solidity of the Golden Age. The sculpture is smooth and devoid of imperfections; it is the smallest in this six-piece series and undoubtedly the most compelling in its simplicity. It tells of stability and perfection: a state of being that unfortunately changes all too easily, yet presents itself in its wholeness before undergoing change. It also reflects the research of a geometrical shape, without processing it too much, by presenting the perfection of nature as such to the viewers’ eyes.

THE MILKY WAY

In addition to being born and dying, human beings also have a mother or mother figure who nourishes them. In verses 168-171 of Book I of Ovid’s Metamorphoses we find the myth of Juno, who spurted milk from her breast towards the sky when suckling the newborn Hercules. The Milky Way was then born, the path which the gods walk to reach Jupiter’s palace. Pablo’s sculpture portrays precisely this moment in which the goddess sheds her milk, creating the Milky Way, which we have all paused to admire with rapt, dreamy feelings on many a summer night. Like many other myths, this constitutes a popular motif which has been taken up countless times in the History of Art. The most famous example is probably Tintoretto’s work in the National Gallery, which Jeff Koons drew upon for one of the last paintings in the Gazing Balls series. Here wood merely reacts in accordance with its own nature. The artist’s eye grasps a torsion, a motion, a spray of vital energy, which once again bear witness to the completeness and beauty of the natural element we are contemplating.

Da sistemare l’italiano (Jeff Koos e ‘gazin balls’)

APOLLO AND DAPHNE

We hear reach what is probably the most famous myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book I. In verse 452-567 Ovid weaves the tale of Apollo and Daphne. The nymph is turned into a laurel tree when fleeing from the god Apollo. It is difficult not to see before our eyes the sculpture by Bernini from the Borghese Gallery in Rome. Here Atchugarry’s two trunks seem to be representing the very moment captured by the Baroque sculptor. The innovative theme is anthropomorphism. This is no longer a creature (Daphne) turned into a tree, but a tree trunk that matches the fleeing nymph’s gesture and turns into nature again. In a way, what we have is a double metamorphosis. The olive trunk raising its branches to the sky mirrors the motions of Daphne as she turns into a laurel tree, just as the knots on the highest stretch of the bark seem match Apollo’s tunic, which flutters in the wind as he chases his beloved.

PHAETON

The myth that brings Book I of Ovid’s Metamorphoses to a close is described in verses 748-779.

Helios’ son Phaeton borrowed his father’s chariot but lost control and set the Earth on fire. This caused rivers to dry up and forests to burn down (the theme of the Amazon crops up again here). This misadventure ended when Phaeton plunged into the Eridanus which many historical studies have identified with the Po. Phaeton’s sisters, the Heliades, turned into poplars because of their grief and shed tears that turned into the amber we now find on the bark of these trees. Once again, then, what we have is a double metamorphosis from the natural to the anthropomorphic, and vice-versa. Phaeton thought he was perfect, being the son of a god, but his lack of attention harmed everyone, gods as well as men. We must take care of the nature surrounding us and these six sculptures made from wood that would otherwise have been disposed as waste, are a reminder of this and offer us a remarkable sculptural operation that marks an evolution in the Uruguayan sculptor’s art.